The Sixth Commandment and Justice

Thoughts on the value and priority of life and the justice of the death penalty.

As I write this (the middle of August) a jury is sifting through arguments, evidence, and testimony that will determine the fate of Nikolas Cruz. Mr. Cruz, 23, pled guilty to murder charges stemming from the shooting at his former high school in Parkland, Florida in February of 2018. That Mr. Cruz is guilty of 17 counts of murder, among other charges, is not in doubt. He has pled guilty and given a public apology - “I am very sorry for what I did, and I have to live with it every day, and if I were to get a second chance, I would do everything in my power to try to help others.” He is not on trial for the crimes committed that day, he is on trial to determine one thing - will he spend the rest of his life in prison, without the possibility of parole, or will he be executed? Some of the victim families want him executed, that is one reason the state moved forward with this trial. Some do not. I have no idea what I would be thinking or feeling in their place.

I was recently in the jury pool for a very similar trial. A Missouri man, a former police officer, had admitted to killing two people and had fired at police officers in his attempt to escape. Nobody disputed what happened and he had been found guilty. Because of a legal technicality, his original sentencing was deemed invalid, and a new trial, with a new jury, a couple of years later, was needed. I was a part of the initial jury pool of 500. After a process that involved a lengthy questionnaire and a week of jury selection, I was in the group of about 60 potential jurors remaining. The person whose jury number was just under mine was the last juror called. I’m not sure if I would have been selected or skipped over, but I am glad I wasn’t selected.

I have a complicated view of the death penalty. The articulation of this view on the lengthy survey apparently did not disqualify me for jury service. Most people are familiar with the injunction against murder in the Ten Commandments. The Sixth Commandment says thou shall not murder - that is pretty clear. That is a part of the moral code that Christians and Jews and Muslims would all agree with. That a Christian is against murder and that murder violates the Judeo-Christian law isn’t a surprise to most. But it can be a surprise to some that, before the Mosaic law was given, the penalty for murder had already been communicated.

And from each human being, too, I will demand an accounting for the life of another human being.

“Whoever sheds human blood,

by humans shall their blood be shed;

for in the image of God

has God made mankind.

(Genesis 9:5-6)

This is meant to show the horrible crime of homicide for what it is - something so deeply wrong that there is no real justice that doesn’t involve the death of the murderer. It is a crime against God as well as a person - an image bearer is killed and the image of God is defaced in the killer. That seems cut and dried. If someone is guilty of murder, they should face the death penalty. This is not part of the Mosaic code that applied only to the administration of ancient Israel - this declaration precedes Moses by many centuries. This biblical command (for the administration of public justice) is still valid.

But, in this real and fallen world, it can seem more complicated than that. That is what I put on my survey, anyway. The death penalty is an appropriate sentence. There may be times when it is the most appropriate sentence. But, there is often injustice in how it is applied. There are times when the death penalty would be an injustice because the defendant is innocent or received an inadequate defense. We know, in the real world, poor people get the death penalty, relatively often, people with means almost never do. And I would have great difficulty imposing the death penalty if there was any doubt as to the defendant’s guilt. In the case I was in the jury pool for and in the case of Nikolas Cruz, though, there isn’t any question about guilt or innocence - and both have excellent legal representation. I am not sure where the correct practical application lies here.

My faith, even a deep understanding of theology (whether I have it or not), does not give me every answer to every question. My faith gives me relative certainty about a pretty small number of issues - what do I think of the Bible? who is God? what about Jesus? how can I know God? what does, in broad terms, following Him look like? what story are we in and how does it end? These relatively few faith commitments, though, are a touchstone for many, many other beliefs and commitments. But for many questions beyond these, we just may not know and we may have to live with not knowing. Does the bible tell us what a Christian should think about the case of Nikolas Cruz - I’m not sure it does, with certainty in every area. But the most difficult question for people of faith related to people who have committed horrible crimes is - how should we think of them as people? What does justice demand? What does love demand? What should be in my heart? This biblical command is not a command for me to avenge or bring justice, it is for a society to address the crime of murder. So how should I, as an individual, respond?

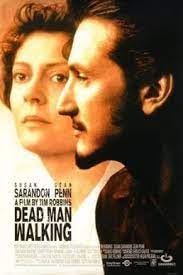

Many years ago, my wife and I watched Dead Man Walking, a movie loosely based on an actual case of a horrible murder of two young people in Louisiana and the relationship between the convicted murderer on death row and the nun (Sister Helen Prejean) who ministered to him. The murderer is played by Sean Penn and the nun by Susan Sarandon. It is an intense, beautiful, and violent movie that unsparingly depicts the pain of a family who wants to let their pain go, a family who demands the murderer be put to death, the sister who helps the murderer grapple with the reality of his deeds, and a killer who finally admits the truth and finds some redemption on the way to his execution. It honestly grappled with the reality of murder and the death penalty. After the movie, we went to dinner and ran into a couple from our church. We didn’t know that one of them was related to a murder victim. Her response to the movie we had just seen was surprising (because we weren’t aware of her situation) and intense. Let’s just say she was in favor of the death penalty. Full stop.

The administration of public justice is one thing, the enactment of justice in my heart toward a person who has committed a great wrong is another. Forgiveness is commanded - but it is commanded individually. My forgiveness is independent of the administration of justice by the state. And it is not my place to forgive the killer of another’s child. Forgiveness just doesn’t work that way. I can’t grant divine absolution and I can’t forgive the wrong another has experienced. But I shouldn’t celebrate the death of another - even of an obviously guilty person. The execution of Ted Bundy was the occasion of a full-scale tail-gating celebration. Crowds gathered outside the prison for the execution, many with signs - “Tuesday is Fry Day!”, “Burn, Bundy, Burn!”, “Buckle Up, Ted - It’s the Law!” It is difficult to understand how we are to think of Ted Bundy, even as he apparently expressed great remorse and turned to God while on death row - not unlike Sean Penn’s character in Dead Man Walking. Just as it is difficult to understand how to think of a remorseful Nikolas Cruz, or of the defendant in the case I was involved in. But it isn’t a celebration of anything.

I have to reject the celebration of this particular enactment of public justice - however appropriate - and I have to reject the absolutist moralizing against the death penalty. I don’t know, given everything, that we have certainty on this one. Murder is a tragedy. An execution is another tragedy. It may the the right and appropriate tragedy, but it is still a tragedy.