The Blessing of Knowing Your Limits

On Humility, Reality, Contingency, Finitude - and the mercy of our unique limits

This may at first appear to be a bit of a "get off my lawn" old man, "back in my day" dispatch. OK, it may be a little. But that really isn't the point I am making. I just recognize that me, my age, my perspective, may easily fall into that bucket - and maybe it is in that bucket a little bit - but I am at least aiming for another one ... you decide, I guess, where it ends up.

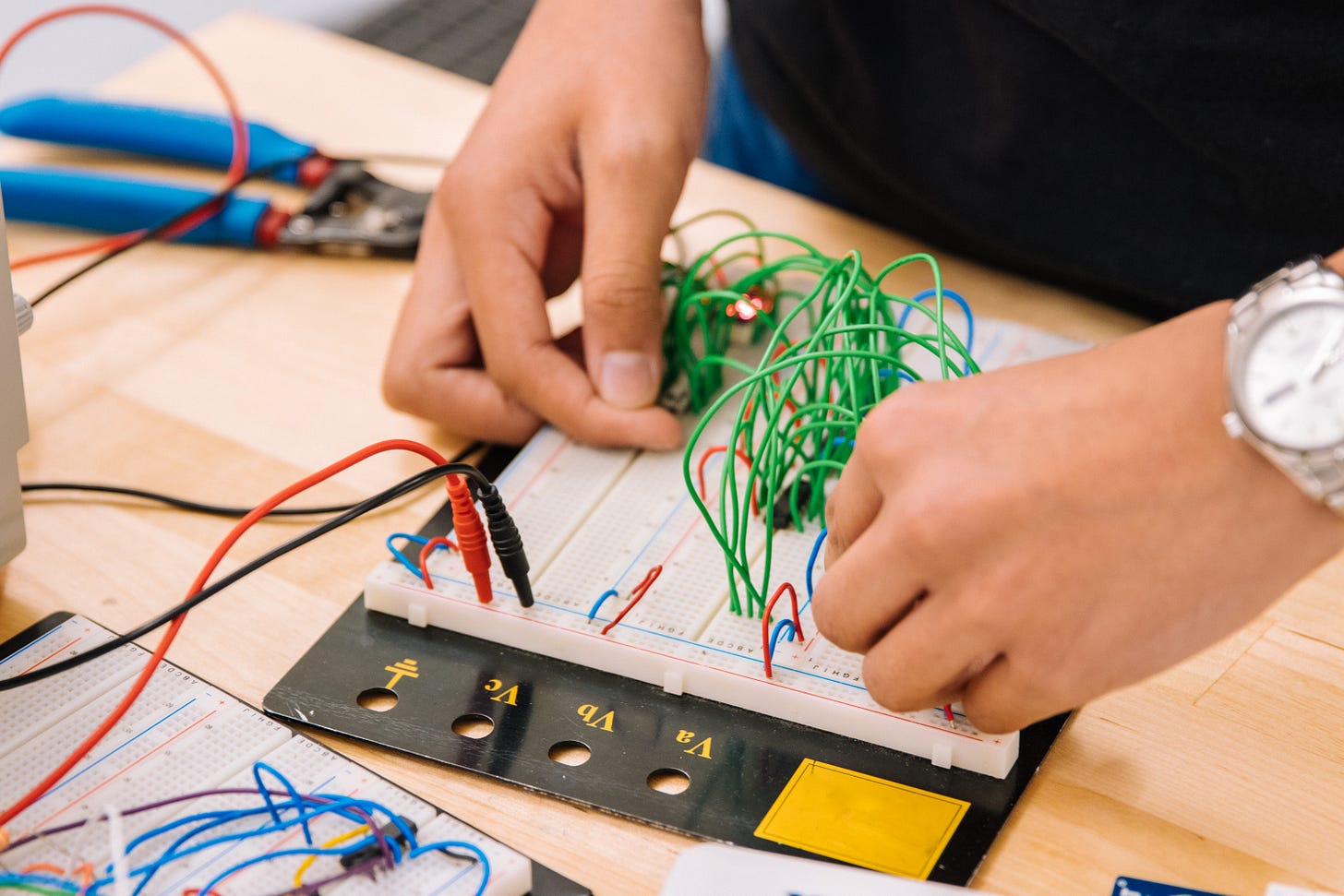

A long time ago, far, far away, I was a student in a 300 level Computer Engineering class at Michigan State University. I had a Computer Science professor, whose name I can't recall but I can picture him and remember him distinctly. He was distinctive. He was a pretty difficult professor. He was unkept, gruff, direct. But he was a good teacher in a difficult course. He knew who he was. He seemed comfortable with his place in the world. This particular class had a big project that was basically pass/fail for the class. You had to get your project working perfectly - and if you did, you would probably get an A. It was a difficult project, very difficult. The class was the first big one for that major on the College of Engineering. If you didn't get your project working perfectly, you had to take the class over. And it was, by design, only offered once per year, so if you wanted to graduate with that major, you were adding a year - at least a year, because there were no guarantees you would get your project working the next year. Or you changed your major (you weren't going to be that kind of engineer - and so, quite possibly, not an engineer at all.) It was stressful. It was designed to be stressful.

I remember this professor having a conversation with a student I knew who was struggling with his project. Struggling might be putting it mildly. This conversation consisted of this professor telling the student that he should probably change his major. That this wasn't the path for him, this wasn't going to work. This class wasn't only a weed out class, but it was definitely a weed out class. It reduced the number of students who were going to graduate with that degree. Prior to admission to the College of Engineering, you had Calculus and Differential Equations and Physics and Chemistry and other classes which (among other things) served to reduce the number of students who were accepted into the College of Engineering. You had to have at least a B average in all the pre-engineering math and science classes to be eligible for admission. All of this was taken for granted by us at the time. It was the way things were. We understood that only about 20% of students who started out college at that time seeking to be an engineer would graduate with that degree. I'm not sure if that statistic was exaggerated, it was the statistic quoted to us at the beginning of our journey. And, if you are not going to be able to do the work of an engineer, it is better to find out earlier rather than later. A junior or senior discovering they won't make it or that they will hate it is worse than a freshman discovering the same truth. There is a certain mercy to it. And a certain recognition of reality. I don't know what the percentage for successful graduation of nurses or doctors or scientists or accountants was, but every field had a bar to reach and what effectively served as weed out classes or obligations. Not everyone who starts on any of these journeys will successfully reach the end - and not every one of them should.

All of this comes to mind in the context of this episode involving a NYU Organic Chemistry professor. The article in the New York Times opens this way:

In the field of organic chemistry, Maitland Jones Jr. has a storied reputation. He taught the subject for decades, first at Princeton and then at New York University, and wrote an influential textbook. He received awards for his teaching, as well as recognition as one of N.Y.U.’s coolest professors.

But last spring, as the campus emerged from pandemic restrictions, 82 of his 350 students signed a petition against him.

Students said the high-stakes course — notorious for ending many a dream of medical school — was too hard, blaming Dr. Jones for their poor test scores.

The professor defended his standards. But just before the start of the fall semester, university deans terminated Dr. Jones’s contract.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Embassy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.