Lost Without Translation Revisited

What Arrival and Shiny Happy People show us about connection, communication, understanding, and translation. And truth. Part 1 in a series.

Due to some scheduling difficulties, we didn’t record a podcast this week. So here is an offering from last summer.

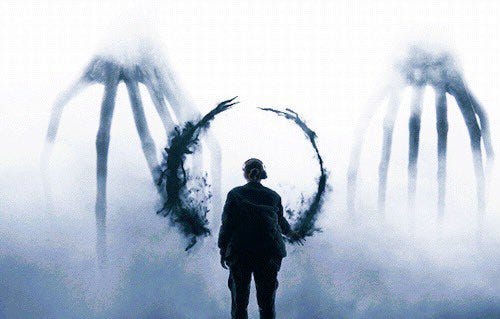

I have a couple of good friends who make lists. Not to-do lists, I do that, but lists of their favorite movies, or of the best TV shows. I am glad for their lists, even if that isn’t my thing. But if it was, I think I would have Arrival, based on the 1998 short story "Story of Your Life" by Ted Chiang, on a list of my favorite movies. It is a smart and surprising story and those who made it had something beautiful and true to show us. It also illustrates something of our times.

The arrival referenced in the title is of twelve sets of aliens, spread across the globe in twelve separate locations. In each location, military and intelligence agencies scramble to make sense of this arrival - who are these aliens and why are they here? Linguist Louise Banks, played by Amy Adams, is enlisted by military authorities and transported to Montana, where one of the alien ships has arrived. Her task is to answer those two critical questions - who are they and why are they here? Similar efforts are ongoing in each location. In one of the locations, because of the assumptions inherent in their culture and communication technique, officials interpret a message as threatening and decide to break off communication. This triggers a race to understand their message before a conflict is triggered by the humans, afraid of what they don’t understand. But it was Banks who doubted this consensus, who swam against this tide of Us vs. Them - and who, in the end, truly understood the message of these alien visitors. It was a message not discoverable through other means - only these aliens could bring it, and, it turns out, it is the key to the survival of the human race.

The movie premiered in the early autumn of 2016 - as the deterioration of communication and the amplification of the Us vs Them dynamic was becoming firmly established in our culture. Just as the military and intelligence authorities in Arrival doubted the ability to communicate and, in the absence of communication, assumed the worst - we often lack the expectation of real communication. Just as some in the film argued for preemptive conflict - not trusting the ability to communicate, we seem to often choose the conflict we know to the understanding we doubt we can have or don’t want. We can assume the worst about what is alien to us. We can assume that understanding is not possible, likely, or even desirable. Real communication involves some level of trust or common ground that gives a basis for understanding. Without some recognition of common ground, without some openness to understanding - we are left with Us. vs. Them. No translation is possible or desired. They are evil, they have nothing to say, they are not us, they threaten us, we must destroy them.

I believe there is something to say and something to hear - that there is some common ground - that real communication, real translation, is possible and desirable. The Christian basis for the belief that there is something to say and to hear is that others, all others, are image-bearers, receivers (acknowledged or not) of common grace. We share a desire for beauty and joy and peace and love found only in God. Whatever someone else believes, I believe that God can speak through all His creatures if he chooses. There is something to say, something of common interest - there is something that draws us together more than takes us away from each other. And all of this makes us profoundly uncomfortable. More than that, this communication, this translation, is part of our calling

The documentary series Shiny Happy People, streaming on Amazon Prime, is about, partly, a way of life that never meant to translate or be translated. It wouldn’t be on any of my favorite lists - even though it appears to be a true telling of an important story. It is just a bit depressing. There is a lot to say about this story, and the related stories of that flavor of fundamentalist evangelicalism - especially from that era, but I want to pick up on an aspect of the Us vs. Them dynamic found here and so many places in our current experience.

The Duggars, first profiled in the 19 Kids and Counting cable series and the principle subjects of Shiny Happy People, relished this dynamic. They (at least the father of the family, Jim Bob - yes, actual name) monetized it. They, and those in that world, insulated themselves by defining their family as different from those on the ‘outside’. Nobody outside that world has anything to say about Us, because they are Them. The world of the Duggars is foreign and that is seen - both by them and by the viewers of 19 Kids and Counting, not as a bug but a feature. From 2008 through 2015, viewers tuned in to watch the Duggars live in their bubble. It fascinated not because it connected to the world of the rest of us, but because it didn’t - and not just because they had 19 kids. This bubble becomes, in their case, a commodity, a spectacle, a product

This bubble also provides the foundation for an unchallenged certainty of thought and action. All bubbles, including the ones we may find ourselves in, do this. And we are all prone to our bubbles - they just don’t seem like bubbles to us. Shiny Happy People isn’t a celebration of the Duggars or of this strain of counter-cultural evangelicalism. It is the telling of how off the rails this world was, or became … how dark, even depraved. The Duggar family’s public fall and fracturing illustrates this dynamic, revealing a deep dysfunction that was there all along - just underneath the shiny, happy image so many tuned in for. For some in the family, their bubble enables a defense of the indefensible - because they are Them and we are Us.

This bubble also provides the foundation for an unchallenged certainty of thought and action. All bubbles, including the ones we may find ourselves in, do this.

None of this Us vs Them bubble dynamic finds any support in biblical Christianity. Christ calls us out of the bubble, not to lose our identity, but to connect with others while being our true selves. Our calling, in fact, is to emulate the fictional linguist Louise Banks from Arrival. We are to reject the example of the strain of fundamentalist evangelicalism that sets itself against everyone else, that not only refuses to connect, but does not see connection as a good thing.

Paul illustrates an uncomfortable picture of what biblical connection, at least in part, looks like.

Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings.

(1 Cor 9:19-23)

Sacrificing the freedom to live apart, safe in our bubble, we are to “become like” those around us - outside of our bubble. Instead of reveling in what makes us culturally different, we are to find a common place to share. To the religious, the irreligious, the lawless, the weak … we are to, in order to connect, to communicate, to translate - in order to carry the truth and grace of the gospel into our world, we are to “become like” those around us. We are to do this without withdrawing (putting our light under a bowl, in Jesus’ words), and without becoming indistinguishable (losing our ‘saltiness’ or savory distinction, in Jesus’ words). Being authentically us, we are to find a common place to connect to the authentic them. In this way, we translate our faith by truly hearing and responding to those to whom we would translate it. We are able to understand, because we have “become like” - and because we are in touch with what it is supposed to mean for Christians to be “authentically us”.

Being authentically us, we are to find a common place to connect to the authentic them.

I don’t have a big enough readership for the above paragraph to be attacked by very online Christians who celebrate all the ways they are different from those around them. But I have seen these attacks … “Oh so you approve of … (fill in the blank)?” - “Aren’t you against … (fill in the blank)?” - “You are platforming … (fill in the blank)” Probably not, probably, and maybe respectively - depending. So what? The irreligious of Paul’s day might practice blood sacrifice or ritual prostitution in temples of pagan gods. He wasn’t “for” that. Again, so what? This isn’t a sorting exercise. (There will be a sorting exercise, but we won’t do the sorting.) It is a mission to translate. Paul does all that he does to “win” them - to facilitate redemptive movement toward grace and truth and healing. This is core to the mission of what used to be called ‘evangelism’ - as in ‘evangelicals’ … but many have forgotten what that word means, or used to mean. How does that work with actual people? Connection. Identification with - without being identical. Bearing the image of God and seeing the image of God in others. Reveling in how God brings us together for His purposes … by all possible means - instead of reveling in how we are distant.

Arrival ends with a final reveal. I won’t spoil it for you. But what the message first appears to be turns into what the message really is. It isn’t a ‘Christian’ message or movie - it is a work of science fiction - but, bearing the image, it holds a truth for us, if we will hear it. But like most truths here in God’s world, you have to try to understand it.