View

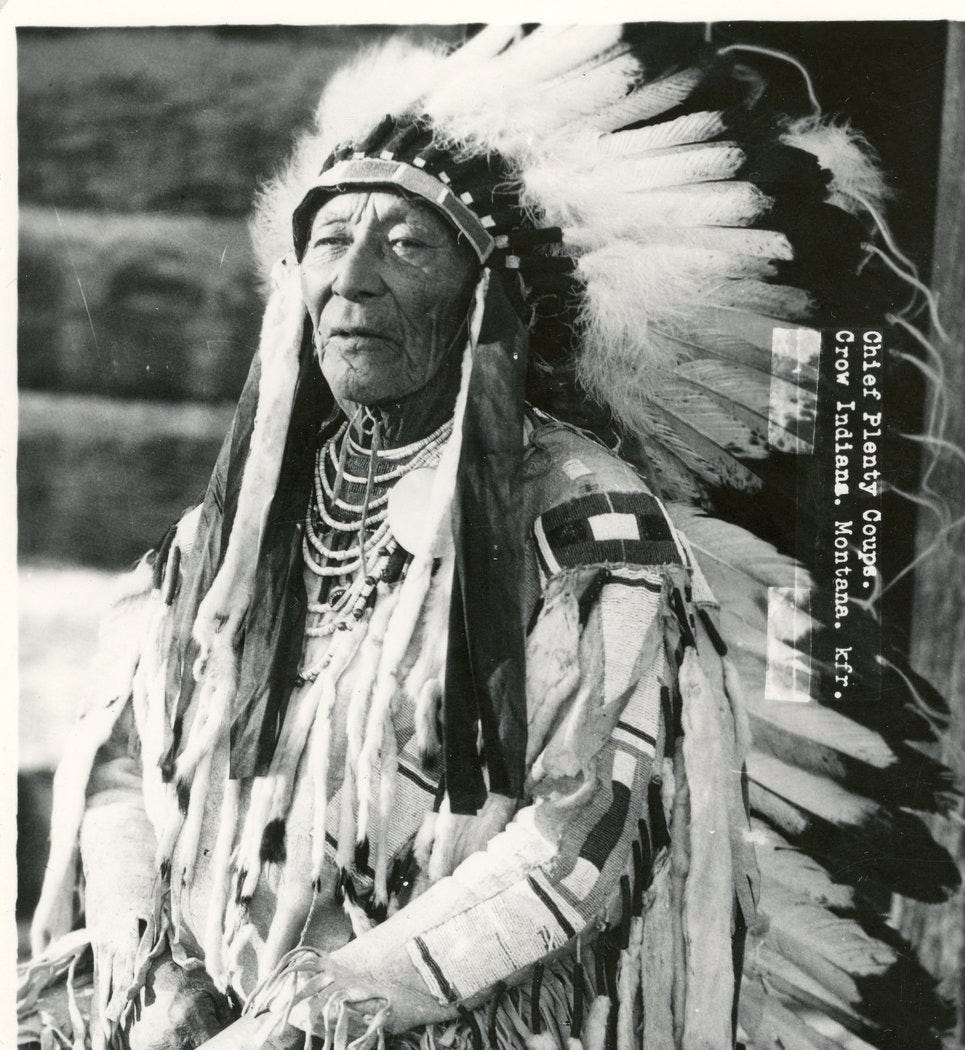

Jonathan Lear, a philosophy professor at the University of Chicago, tells us of a conversation in which the last great Chief of the Crow Nation, Plenty Coups, spoke of the history of his people - specifically the end of the history of his people. At first, he didn’t really want to expound on this ending. Not only because it was too painful, but because there wasn’t, from his perspective, much to say.

I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. Besides, you know that part of my life as well as I do. You saw what happened when the buffalo went away.

Chief Plenty Coups, from Jonathan Lear’s Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation

Anne Snyder, editor-in-chief of Comment magazine, reflects on Lear’s book and how Plenty Coups’ quote - “after this, nothing happened” - haunted Lear. Lear’s book focuses on the vulnerability we face as our way of life breaks down, or when we think it is breaking down. I could make the point that it was our ancestors who made the buffalo go away and thus caused the hearts of those peoples to fall to the ground. It would be a valid point. But here I want to think about our own vulnerability, by our own hand or the hands of others - that our own way of life is ending, or, perhaps, has ended. Our buffalo are disappearing, mostly by our own hand. Lear says of this vulnerability -

We seem to acquire it as a result of the fact that we inhabit a way of life. Humans are by nature cultural animals: we necessarily inhabit a way of life that is expressed in culture. But our way of life - whatever it is - is vulnerable in various ways. And we, as participants in that way of life, thereby inherit a vulnerability. … How ought we to live with this possibility of collapse?

Jonathan Lear - Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation - 2008

We are faced with this question - how ought we to live with this possibility of collapse? Snyder ruminates on the ways in which our faith tradition, confronting this question, can get co-opted by narratives of nostalgia leading to withdrawal or to attempted dominion, narratives of revolution tending toward a tearing down of all things current, or narratives of nihilism tending toward passivity and inaction. None of these line up with a Christian understanding of our world. Christ came to bring something new - to usher in a new age and to point to a coming one. He came to bring direction, purpose, and hope to all who will follow Him - those under the yoke of the Roman Empire, and those under the yoke of their own devices.

For many people, the ‘this’ in “after this, nothing happened” might be represented in the millions of people flocking to see Oppenheimer with all its fiery imagery. Or it is the 60’s, or the 70’s, or the adoption of social media as a primary means of communication and understanding, or the (perhaps accompanying) degradation of our political order, or our cultural order, our institutions, the debt, the climate, AI, even the drop in fertility. Our way of life is vulnerable. This is a good thing, if we will accept it. Something that is a loss, but that is redeemed by what follows. But we can wed ourselves to an understanding of what our way of life should be that we can only see the loss. Or we are so frightened by this vulnerability that we refuse to see it and are, as a result, undermined by an atmosphere of unattached anxiety. Our culture can respond to this anxiety in all sorts of ways.

Journalist Suzy Weiss chronicled one of these responses, labeled “Doomer Optimism” by adherents. She attended their second annual gathering earlier this year in Story, Wyoming to see how they would describe this trend. There she found homesteaders, venture capitalists, law students, preppers, and ecologists. Parenthetically, I wonder how the Preppers respond to this trend. They were doomers before it was cool - although I’m not sure they have been characterized by optimism.

“If you’re not familiar with the milieu, you might be like, ‘What hangs all these people together?’ ” Ashley Fitzgerald, 39, one of the organizers of the conference, told me. She coined the term Doomer Optimist in a tweet on January 23, 2021, and since then it’s come to summarize what they all have in common.

First, they’re doomers. They believe that we’re at “the end of industrial modernity,” said Fitzgerald, or “the end of the end of history,” or they think that liberalism is over, or that we’re living within “a collapsing global empire”—a million different ways of saying that, in short, we’re screwed.

Second, they’re optimists. Collapse could be a long process, Fitzgerald assured me. “And maybe it’s not even collapse, maybe it’s just a transformation.” And everyone in this cohort, she said, is trying to live a good life, to forge ahead, despite their doomerism—“trying to find meaning in an alienated world.”

Suzy Weiss - The People Who Rage Against the Machine - The Free Press - September 17, 2024

Trying to find meaning in an alienated world. I’m not a Doomer Optimist, but that is actually pretty good. In fact, the Christian narrative offers meaning in an alienated world. More specifically, the Christian narrative of the end of all things, the Christian apocalyptic message is what we have forgotten in our alienated world. We have the apocalyptic message, certainly. In fact, much of our apocalyptic understanding had roots in this Christian understanding - but it has escaped, in what Jonathan Askonas called “kind of a theological lab leak”, its proper context.

Of course, the word “apocalypse” comes from the Christian narrative, even as it is used in our secular analysis of history. One of the central biblical meanings of the word is an in-breaking of God’s presence in this age that ends it and ushers in another. It is part of the Christian narrative. For the secularist, apocalypse is bad in any sense of the word. Not only that, all the agency lies with us and, therefore, all the responsibility to avoid apocalypse and usher in utopia. This has resulted, many have argued, in our increasing anxiety - one false move and all is lost. For the Christian, we believe an apocalypse is certain and necessary for the full redemption and restoration of all things - utopia is not in our grasp and apocalypse is not in our ability to avoid. We are called to faithfulness in presence and service and transformation by God’s power as preparation for any future, including an apocalyptic one.

For Christians, the drawing near of the apocalypse should serve (as it has throughout history) not to paralyze us or make us anxious but to spur us to bold and hopeful action. The end is coming. There will be a catastrophe. But providence still ordains that all will be well. In the Greek myth, when all the evils have fled Pandora’s box, what remains inside is hope.

Jonathan Askonas - Building a Future in the Face of the Apocalypse - Comment - Fall 2024

The New Testament biblical response to the prospect of apocalypse, this coming of Jesus to us is one of hopeful anticipation - even if it means the overturning of the world as we know it. In part because of this overturning. This is the way that justice is done, all is restored, and the brokenness of humankind is healed. Of course, it is true that throughout history and throughout the world, the church has and does most often occur in contexts of poverty, sacrifice, or persecution. Apocalypse means the end of all of that - and therefore perhaps more naturally viewed with hope.

Many parts of the Christian narrative refer to this apocalypse, but the book most centered on it is Revelation, the last book of the Bible. After all the overturning and all the restoration has been described (however apocalyptically or symbolically), the book - and the Biblical narrative - end with a hopeful call for “in-breaking”, this apocalypse, the return of Jesus. “Come, Lord Jesus” is the closing message of the Bible.

This, for the Christian, is where we live. In the hopeful shadow of the apocalypse. While this or that way of life might end - however attached or repulsed by it we might be - it is not the end of all life. After this, things will happen. We are not called to preserve a certain way of life but to move forward toward God’s call and the mission of the church. In the hopeful shadow of the apocalypse.

Links

Defying Decline - Anne Snyder - Comment - Fall 2024

Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation - Jonathan Lear - Harvard University Press - 2008

The People Who Rage Against the Machine - Suzy Weiss - The Free Press - 9/17/2024

Building a Future in the Face of the Apocalypse - Jonathan Askonas - Comment - Fall 2024