View

I’ve been wanting to write about men and masculinity in our culture for some time now. I haven’t yet for a number of reasons that I will mention in a minute. But an unexpected juxtaposition has presented itself. First, there recently has been a number of excellent explorations of how men, young and old, of all ethnic groups, are struggling. There are too many to mention. Here is an Andrew Yang piece from last year, here is perhaps the most talked about piece (and perhaps the best one) from Christine Embe at the Washington Post. Here is a follow up discussion between Embe and Richard Reeves, who wrote a definitive study of the struggles of men - Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It. Politico even devoted an entire issue to it. There are a number of things about these pieces to note - one is they are all from the left of center politically. Many of the pieces decry how the right and far right have attracted disaffected men, but now all sides of the political spectrum look at the data (outlined extensively in Reeve’s book) and take notice. Reeves himself is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, a left of center think tank. The second is that the issue became one much more openly discussed after women began writing about it. Embe’s piece is excellent, which is one reason it received so much attention. Another, I think, is that she is a left of center journalist who is a woman - giving a permission structure for discussing her piece when earlier pieces (and Reeve’s book) did not receive the same attention - especially from left of center sources. If you look at the Politico issue I noted above, you will see that all of the named pieces are written by women. I have to confess that one of the reasons I haven’t written about this issue is - well, I am a man. I don’t want to be coded into the culture war alongside some (rather strange) figures as just another man complaining about how men are faring. I don’t usually let things like that impact what I write about, but there it is.

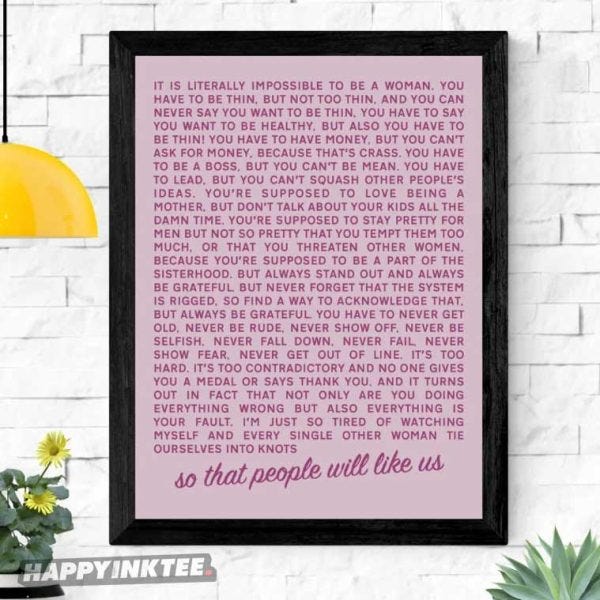

All of that is the first part of the juxtaposition. The second is that “Barbie” was released this summer and became the most popular movie of the year - and one of the most talked about. (Not that it bears on my point directly, but I want to say that I think “Barbie” is a very well done movie - it would have been easy to make a bad “Barbie” movie and this one is good.) “Barbie” isn’t about men of course, it is mostly about women, but it seems to be saying that how gender works itself out in our culture isn’t working. It gives this viewpoint from mostly a female point of view, highlighted by the speech that awakens the sleepwalking Barbies given by America Ferrera’s character, Gloria. This female “not working” represented in the speech looks like a world of impossible and contradictory expectations - setting up women to fail. The male “not working” is not as prominent as a theme - this is mostly from a feminine point of view - but it shows men as hapless, menacing, or irrelevant. The counterpoint to the speech from Gloria is the performatively irrelevant role of her husband in the film. (Which turns out to be her actual real life husband.) He wasn’t left out of the movie, but seems to have been included in order to highlight his, well, performative irrelevance. Even the “patriarchal” role reversal led by Ken (ok, listen, if you don’t know what happens in “Barbie” by now I can’t help you) is mostly to gain the favor of the Barbies and, in the end, doesn’t work.

At the end of the movie, Barbie is set free by her female creator and enters the real world as a real (and single) woman. She does this after letting Ken know she doesn’t need or want him. It is this last part that we are perhaps not paying close enough attention to - and which may overlap a bit with the first part of the juxtaposition. Whatever else it does, “Barbie” depicts a world where women don’t need men. And, in the mirror of Barbie, often portraying a truth about one gender through its opposite, it is a world where men don’t really need women. And that seems to reflect so much of our time, especially among the young. I am not referring to the number of recent pieces that depict an openly hostile stance toward men, some even celebrating their mutilation or death. Even setting those aside, we seem to find ourselves in a moment where women and men are often coded on the opposite sides of the culture war, and many respond accordingly.

Less than half of single adults are looking for a relationship - and the share of single men looking for a relationship has fallen more than 10% in the last three years. Ten percent in three years is a lot in a short time. At the same time, Ross Douthat points out that our self-reported happiness and the marriage rate have gone down together. Whatever the causes and correlations, it seems significant to note that we are more independent, and that we are less happy.

Men withdrawing from relationships with women is part of a larger trend of men (noted above) checking out of the workforce and career advancement, checking out of college and post-graduate studies, and checking out of life. Thus the recent flurry of reflections on how men are struggling in all sorts of ways. These struggles lead to the checking out and the checking out leads to more struggles. One of the things men seem to be checking out of, consciously or not, is eligibility for relationships with women. And most of this happens under everyone’s radar.

Whatever the causes and correlations, it seems significant to note that we are more independent, and that we are less happy.

What Gloria articulated in “Barbie” named something for many women. My wife Nancy and I were in a crowded theater and we could hear many women respond to it. I’m not sure there is such a speech for men. Men who aren’t on a team or platoon or other group, even a friend group together, don’t think of themselves as in a brotherhood. In my experience, men experience other men as being in an unconscious hierarchy with them. (A friend of mine who I worked with years ago would regularly pit two other fellow male staff members in imaginary pugilistic combat and ask the room who would win. We all had our opinions. We didn’t hate it.) Men who adjust well to this hierarchy have a way of finding their place among other men in a manner that is automatic and subconscious. Men who don’t find their place among other men have trouble adjusting to the world, don’t tend to have a healthy self-image, and don’t tend to have positive relationships with women. If there is something to be named among men, it is the need to have purpose, to be useful, to find a place, to be needed, even. “Barbie” depicts Ken as bemoaning his lack of purpose and the fact that Barbie does not need him - even that he has no identity without her. “It is always Barbie and Ken, never just Ken.” This can be interpreted a number of ways - including a representation of the experience of women in the upside-down world of the movie, but I believe it resonates with men as well.

It is always Barbie and Ken … (Ken)

The response to the movie has been significant - and, like anything in the culture, can find itself expressing the ongoing cultural war of all against all where everything takes on a conflict posture. I have heard in conversation and read more than once that “Barbie” is an anti-man movie. That is a culture war take for which, if you look, you can find fuel. Like most culture war takes, you can generally find what you are looking for if you look hard enough. But I don’t think it is a movie that is against men. It isn’t about men, it is trying to say something about women first, but also how relationships between men and women at scale don’t seem to be working for men or women. That is difficult to disagree with when you look at the sociological data. (For those looking for a movie that is anti-male, “Men” works much better than “Barbie”). But at the same time many women (and men) seem to take the position that masculinity (which men are born with to some extent) is assumed to be toxic. How are men to respond? Who are they to be? Must they deny something intrinsic to themselves to fit in?

If so, as Reeves and others have noted, it isn’t working. Men are doing worse at school, in college, in the workplace, and in relationships - worse relative to any definition of flourishing. One area where men are increasing is deaths of despair (which are suicides, overdoses, and alcoholism). Men have always committed suicide significantly more than women, but last year men accounted for almost 80% of suicides. Something is wrong, but it is difficult to say something is wrong without appearing to be making some sort of culture war statement.

We have trouble depicting masculinity in positive terms. In the first season of “True Detective” (one of the best artistic depictions of the conflictions, contradictions, and struggles of men to be found), Marty (played by Woody Harrelson) wonders (with some reason) if he is a bad man. He asks his partner Rust (played by Matthew McConaughey) if he ever wondered if he was a bad man. Rust replies that he does not wonder. “The world needs bad men. We keep the other bad men from the door.” It is an arresting picture. And most men would confess that it is a romantic one, appealing at some level. We would have to confess it, because we would be admitting to being a bad man - even if for a good reason. I would guess that almost every man who watched the series knows immediately what scene I am referring to. It is the man who does what is necessary even if it is regrettably necessary - the Dark Knight who is the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now..

The world needs bad men. We keep the other bad men from the door. (Rust Cohle)

A classic example of this unhealthy yet appealing picture of masculinity is the quiet man in the Old West who rides into the town overtaken by bad men and who rescues the town by taking care of the bad men. (“Taking care” here means shooting them - which is what Rust probably meant also). “Taken” is another movie franchise depicting a flawed and lonely masculine figure rescuing the vulnerable. “Reacher”, “John Wick”, and others all have the theme of a (possibly bad) man doing whatever it takes to achieve justice. Justice might be defined loosely (John Wick killed 77 people because they killed his puppy. That was just in the first movie. The franchise total stands at 439. The SAG-AFTRA strike may be the only thing preventing more carnage. On the other hand, super cute puppy). “The Equalizer” represents a modern equivalent of the rider of the Old West. Denzel Washington plays everyman Robert McCall who “equalizes” (and not via negotiations) unjust situations. In the first movie of the franchise, he is asked about the book he is reading, and he replies “It's about a guy who is a knight in shining armor, except he lives in a world where knights don't exist anymore,” possibly referring to Don Quixote, or maybe just a rider of the Old West, but most certainly he is describing himself.

Key to the classic savior of the Old West picture is the man riding off alone. More towns to rescue, and all that. Both Rust and Marty end up alone in a sense. In another sense, they end up with each other. Even in True Detective, we see again that man was not meant to be alone. It is a sad irony that many disconnected men live out this masculine picture virtually, through a screen, sitting in a room, alone.

What is a positive picture for masculinity? Before giving a couple of thoughts in response to that question, remember that any positive picture of masculinity can be taken and turned into a culture war take … “are you saying women can’t be _____?” No, I’m not. I am trying, probably unsuccessfully, to describe a positive picture of masculinity that other men can take some cues from. Nothing more.

Men should protect, provide for, take responsibility for, and sacrifice for others. As with all virtuous actions, they should not seek to be noticed doing so. In Ephesians 5, the apostle Paul says that a man should lay down his life for his wife. Laying down your life is the highest measure of love we are given - so that is just one application of a general principle: my life is not about me. Married or not, the question of who I am serving, loving, helping should be central to men and women - but it isn’t a natural question for men. Incidentally, Paul does not favor married life over singleness (1 Cor 7), but this just frees the single person to answer these “kingdom” questions without respect to caring for a spouse. In all cases, the life of flourishing described to us in Christianity is a life in community - serving together, praying together, learning together in a way that is for others. It is in this context that the (perhaps) masculine impulse to protect, lead, provide for, and work for justice can find its rightful place.

My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. (Jesus - John 15:12-13)

It is easy to say that disaffected, alienated males become criminals generally and serial killers and mass shooters more specifically. That is true. But the problem extends in a different way to many more men, perhaps most men. The path for my life is largely set, I am not concerned for me. I am concerned for my sons, son-in-law, grandsons, and younger friends as they grow up and live in a world in which it is increasingly difficult for them to find their place. Men, in addition to relationships with other men, need to be in loving relationships of mutual responsibility with women - their mothers, sisters, wives, daughters, and other significant women in their lives. Without this, their lives are impoverished. With this, they are less likely to be at war with themselves and with the rest of the world. Men are generally bad at this. But it is also true that women flourish as they are in such relationships with men - with their fathers, brothers, husbands, sons, and other significant men in their lives. Can a woman live without a man? Of course. But a life with meaningful relationships among men and women is an unambiguous good. It is the opposite of an ongoing war of all against all. We are to be for each other, for a shared purpose, for a shared community, for shalom among men and among women and among men and women together.

The end of “Barbie” does seem to describe our current moment. But I hope it doesn’t endorse it. We need each other. That is a good thing. Specifically we need men to be purposefully integrated into the world around them. And that purpose must be for others and for the good of the world. That is where masculinity can find a home.

Links

Men and Petite Maman are polar opposite fairy tales - Ross Douthat, National Review

The Church in a Time of Gender War - Samuel James, Digital Liturgies

Gender War, Technology, and De-Centering the Self - Samuel James, Digital Liturgies

Men are Lost. Here’s a map out of the wilderness - Christine Embe, Washington Post

Transcript: The Crisis of Masculinity - Christine Embe and Richard Reeves, Washington Post

The data are clear: The boys are not all right - Andrew Yang, Washington Post

Of Boys and Men - Richard Reeves, Brookings Institute Press

The Masculinity Issue - Politico

Why Ken and Barbie Need Each Other - Ross Douthat, New York Times

The Struggles of Men are a Problem for Everyone - Jeff Haanen, Christianity Today